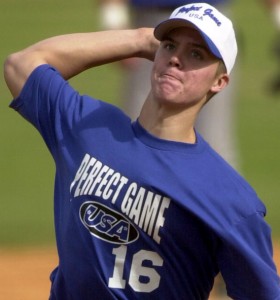

Feature Photo: Zack Greinke (Photo by Perfect Game)

In the third installment of our PG in the Pros series, Perfect Game’s David Rawnsley profiles the unique path that took high schooler Zack Greinke out of the infield, onto the mound, and into becoming a perennial Major League All-Star.

The most intriguing part of Zack Greinke’s development as a baseball player, indeed, the most dominant part of his development, was that he didn’t want to be a pitcher. In fact, he virtually fought being a pitcher as a teenager, and one suspects that desire to be a position player involved in the everyday flow on the baseball diamond as part of a team might have contributed to some of his early professional struggles on and off the field.

The most intriguing part of Zack Greinke’s development as a baseball player, indeed, the most dominant part of his development, was that he didn’t want to be a pitcher. In fact, he virtually fought being a pitcher as a teenager, and one suspects that desire to be a position player involved in the everyday flow on the baseball diamond as part of a team might have contributed to some of his early professional struggles on and off the field.

Greinke was a primary shortstop at Apopka High School (Orlando, FL) and hit over .400 with 31 home runs during his high school career. He pitched in relief as a sophomore and junior, but he didn’t start games on the mound until his senior year.

His problem as a position prospect was that Greinke couldn’t run. He was a very solid hitter with lots of power potential. He had athletic, balanced actions on defense and his arm, not surprisingly, worked beautifully in the infield. But he was a 7.4 runner in the sixty, and his first step on balls was neither quick nor projectable. Picturing him as a professional, Greinke projected as a third baseman at best.

At the 2001 Perfect Game World Showcase, held just before his junior high school season, Greinke played some catcher in addition to his work at shortstop. He looked like a natural in the catcher spot, popping 1.85 during drills with 83 mph arm strength. Scouts frequently had Greinke work out behind the plate, although his build wasn’t ideally suited for the rigors of the position. But his athleticism and tools profile, with the big arm strength, soft hands and the lack of foot speed, made catcher a natural position to speculate about.

Of course, Greinke also took a short trip to the mound during that 2001 showcase – and promptly hit 94 on the gun with his fastball, with clean and easy pitching mechanics. That just further teased the scouting community about his potential on the mound, although it was commonly felt that he had no interest in being a primary pitcher.

Greinke committed to Clemson University after his junior year. At that point, he looked like the kind of talent who would best define himself after the benefit of three years of college, likely playing in the field while developing as a pitcher. He played at the 2001 WWBA World Championships in Jupiter, FL (for the East Coast Scout Team) and played shortstop, except for one appearance on the mound that was specifically requested by scouts.

Greinke’s obvious talent on the mound combined with the Apopka High School team’s needs planted him firmly on the roster as a starting pitcher for his senior season, and that’s where the final transformation from “Zack Greinke, The Reluctant Pitcher” to “Zack Greinke, the Premium Pitching Prospect” finally took hold. He went 9-2 with a 0.55 ERA, striking out 118 hitters in 63 innings. Apopka went 32-2 and Greinke was named the Gatorade High School Player of the Year.

The last time I saw Greinke play as a high schooler was at the 2002 Florida State High School All-Star Game in Sebring, FL in late May. Two things stood out about this event. First, it ranks in my own personal top 10 of hottest baseball experiences ever, with temperatures in the upper 90s and high inland Florida humidity being almost unbearable for three full days at the field. Second, the talent level was absurdly high. Ten Florida high school players were picked among the first 74 selections in the 2002 draft, including first-rounders Prince Fielder and Denard Span. It served as a virtual national convention for scouting directors, with a couple of general managers mixed in.

Greinke was magnificent on the mound and seemingly immune to the conditions – or the all the eyes on him – in the antiquated Sebring ballpark. He sat in the mid-90s with his fastball, threw his breaking ball for strikes and seemed sweat-free, while scouts were reaching for their 10th bottle of water of the day. I vaguely remember one hitter who took a few good cuts at some early Greinke fastballs until Greinke just sort of shrugged his shoulders and simply walked it up the velocity scale…94, 95, 96… until he found one that the hitter couldn’t handle.

Fast-forward to the 2002 MLB First-Year Player Draft, and the Kansas City Royals picked Greinke with the sixth overall pick, one pick after the Montreal Expos selected another high school right-hander, Clint Everts, but one pick ahead of Fielder by the Milwaukee Brewers (the Pittsburgh Pirates selected Bryan Bullington out of Ball State University with the first overall pick). Greinke was playing in the 2002 WWBA 18U National Championships in July for Team Florida USA, and notably not pitching (playing shortstop), when he agreed to a $2.5 million contract.

Strictly by coincidence, I happened to be at Baseball City, the Royals innovative but now torn down minor league complex west of Orlando, when Greinke suited up for his first professional game after signing. Greinke, of course, didn’t pitch. But the player I was there to see told me an interesting story after the game. The Royals Gulf Coast League (Rk.) manager was a crusty old veteran named Lloyd Simmons, who was, prior to joining the Royals, a legendary coach for 26 years at Seminole Community College in Oklahoma.

Greinke evidently spent the entire game with a bat in his hands, standing up and taking practice swings and doing everything but coming up to Simmons and asking him to let him go to the plate. Eventually Simmons cracked. He walked up to Greinke late in the game and told him “Son, if I ever see you with a bat in this dugout again, I’ll (insert suitable but impractical phrase familiar to all baseball players). You are a pitcher and pitchers don’t hit here!”

Thus, somewhat rudely, did Greinkes’ dreams of hitting probably start to fade from reality. It should be noted, however, they he never lost his feel for the bat – he is a .220 career hitter with six big league home runs to his credit despite all the years he spent in the American League.